Marilyn revealed…

“How are you Lester? Did your Amaryllis Bloom this year? Mine didn’t–it’s a little like me. But maybe there’s still hope. How late do they bloom?”

Excerpt from a letter from Maryiln Monroe to Lester Markels, Sunday editor of the New York Times. From the personal possessions recently rediscovered in Monroe’s file cabinets. Photos by Mark Anderson.

Some are more whimsical……

Here’s a recent piece I wrote on the autopsy photos of Marliyn.

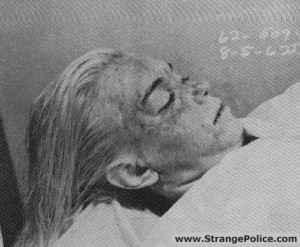

The are two autopsy photos of Marilyn Monroe; one is shot from above–this could be a snapshot of her younger self; a little baby fat, heavy brow and mascara, full face, cheekbones less defined. The other is in profile; the face is puffy, bloated, the skin mottled–a pattern of marks like large freckles or age spots scattered on her forehead and checks. She has a double chin in the photo, a white sheet pulled up snug to her chin. Now the iconic eye liner is faded. The hair is flat straight and wet, the buoyant curl lost, slicked back evenly, medicinal hands pressing back hair, pushing it out of the way. The first photograph is of a young girl asleep; she’s pretty, fresh faced and clean, her expression serene, simple, she drank too much at the party and passed out on the couch, her makeup still intact.

The second photo is a woman in early middle-age, she may have overstayed her day at the beach; the upper part of her face looks sun-burnt and blotchy, his lips flat and plain. It’s as if she had just left the water, stumbled back to the shore, settled on a towel and soaked up more of the sun, a beached person thrown back from the sea. You can compare these photos to the famous series taken of her on the beach in Santa Monica by George Barris a few days before her death–this is Marilyn at her best; breezy, casual, languid, beautiful, sexy but comfortable. She smiles up at the camera, a pursed but happy smile, she’s teasing the photographer a little. Her hair is blowing, wavy, unkempt, her eyes made-up in her signature black liner but slightly casual this time, drawn easily over the eyelids, sloppily, as if she’s just woken up and reached quickly for the liner. She throws on a sweater, a wrap-around Alpaca, it makes the photos look modern, later then 1962 the year they were taken. After the photo, she pushes her hair out of her face and looks up, Is this is me? She says, then she dives into the water, takes a short swim, a few quick playful strokes, runs back to the shore and lies down on the beach, her hair slicked back, a bright sunburn spreading on her checks and forehead. She pulls a towel up to her neck and falls asleep, he snaps another picture. He knows she will hate this picture.

Noguchi, the coroner who performed her autopsy, was born a year later after Marilyn, in 1927. While Monroe was in foster homes, he grew up affluent in Tokyo–he left Japan shortly after the war, came to America. While he is young and finding work in California, Marilyn poses naked for a photographer, Hefner uses it for his first issue of Playboy in 1953. Noguchi buys the magazine, it is the first American magazine he has ever bought. A little embarrassed, he slips the magazine out of its wrapper, she is naked, lying sideways on a background of red velvet, her arms spread out raised above her head, as if languidly reaching for cigarette, her private areas covered by the pose. The red background startles him, he is used to black and white shots of demure Japanese women discretely slipping off kimonos, antique vases and floral furniture placed conspicuously around them.

Marilyn starts appearing more places, this time a baseball player at her side–Joe DiMaggio. Noguchi’s a baseball fan but he’s worried, DiMaggio looks tall, spindly, his nose too large for Marilyn’s delicate features, a cardboard cutout stuck next to a voluptuous figure. Ten years after arriving, he was performing an autopsy of the most famous woman in the world. He is young, inexperienced, an outsider, she is less then a year older then him–thirty-six, and is now case number 81128. It is his first celebrity autopsy but he feels he is looking at a contemporary–someone he has passed time with vicariously, he had watched her in the spotlight, she is so young. A year later Kennedy is shot, he’s not sure of the association with Marilyn, there are rumors, he doesn’t perform the autopsy but sees the photos, reads the report, he feels stranded, stale after the photos, feels like reaching his hand in and tinkering, evaluating, but it is not his autopsy. Six years later, he is standing over Robert Kennedy removing pieces of bullets from his brain, it is believed Marilyn is his lover at the time of her death. He couldn’t help compare the two, each laid on the slabs, while Marilyn became someone removed from herself– bloated and aged, Kennedy looks the same, the same gangly boy sleeping on a slab, two of the most famous people in the world, he had only met when they died. Two deaths associated with conspiracy theories he either has quelled or instigated, Marilyn he feels is suicidal yet Bobby is associated with Marlyn’s death and in Bobby’s death he sees two shooters, not one.

The autopsy photographer–let’s call him John Brown; J.B are the initials written hastily across the photos–could have taken his children to the same beach, the same day. When Barris shot Marilyn, he was at the beach, a jetty or two down, his kids running around him, thinking about the man he just photographed yesterday, it was ordinary death, a man who had choked, his face had looked paler then usual, bluish lips always bothered him. He and Noguchi had been joking that the job was getting boring, weighing hearts and organs with little interest. John is lolling on the sand, nibbling sandwiches, dipping in the water periodically. Nearby, George Barris is standing beside Marilyn, the two are chatting, watching the waves, the light is bright and even with little shadow. Two photographers preparing for an aftermath on separate days, how was he to know a day later he would snap photographs as well, continue the coverage of a star. When Brown snaps the photos he doesn’t feel disheartened more stricken that her beauty had drained away, they’ve taken their equipment and sluiced away the beauty–the icon. Noguchi calms him down, he had seen so many dead. But he is quiet the rest of day, in the morning he will face the press, questions of cause of death. Brown takes a swim, the water feels heavy around him, his wife and children jump on the sand behind him, as the water spills over him and he thinks of Marilyn Monroe, wondering why she’s fallen for that writer, Miller, he doesn’t go to plays, he doesn’t understand intellectuals, Noguchi is like Miller, smart and dry, he is too dark for Marilyn, maybe Paul Newman would be better or Rock Hudson. He looks at his wife, she is bleach blond like Marilyn, similar hairstyle, but she is heavier, stockier, louder, perhaps unhappy like her.

Noguchi married young, the ceremony simple but colorful, he met his wife in the white light of the west, a hard Californian glow but she looks nothing like Marilyn, she is dark haired, svelte, forlorn and wistful. The DiMaggio-Monroe wedding photos come out in the paper, they look at them together but his wife is indifferent to Marilyn, she’s more interested in DiMaggio, she finds him impressive, his height regal, he is a gentleman. She doesn’t understand why Marilyn wears a suit, could be going to a funeral or an office she says. Later he reads DiMaggio beat her after the famous dress-blowing scene from the Seven Year Itch. He can’t imaging anyone hitting the likes of Marilyn Monroe, the act itself seems unworldly– slapping the most famous woman in the world, but he still likes the title of the film.

And now as he weighs her heart (300 grams) he feels bittersweet–a trademark feeling he seems destined to bear, it goes with the trade he thinks, his life had traces of pleasure but they were brief, migratory, swift, fleeting with silver traces of pain, not one emotion overriding the other, it was a constant even-keel of being in the mirth of pleasure yet there seemed a trace of exertion, a sweet pain lolling about him. All autopsies left him with this feeling, you remove the lungs, the heart, only the cavities remain, dead space, dead weight, an emptiness but you’ve done a service, you’re a proud man, happy man even. He’s sick of John Brown’s chatter, the way he holds the Stryker saw over her chest and breathes through his nose is excruciating, stick to the photos he thinks, that’s progress, documenting death not slicing into it. He wants to divorce himself from the celebrity autopsies, the dead are the dead but he’s not so sure, he can’t shake Marilyn’s image from his mind. He is sad this is the image that is left with him, flesh left on a tray, the substance within betrayed, gone, ousted out by professionals, forever gone is the wispy voice and fertile sleeve. He compares bodies to husks now although by holding organs and recording data, he feels better. This autopsy was different, usually he’s able to disassociate himself, but as he works, he is distracted by the hair, it’s all wrong now, gone is the short wavy bob, now it is flat, severe and the hands are dull, her painted pink nails too bright against the skin.

He watches the funeral on television, he wishes TV was in color, the impossible amount of flowers seem like props, plastic and stiff in the shadows. Joe DiMaggio is leading the coffin, then later looks like a wounded animal in the back of his limo–he’s not sure he has ever seen DiMaggio smile, often the brows are knitted and suspicious when around Marilyn like he’s a jumpy bodyguard on the prowl. Noguchi feels almost ashamed DiMaggio is there and not Miller, why is DiMaggio superior to Miller? He likes neither men, but feels the staid Miller should have been there in the shadows, discreetly crying against a tree during the service. His wife is visibly upset, but he isn’t sure why. His wife doesn’t ask questions about the autopsy, she used to at first, puzzled by his occupation, fascinated by the details of the body, the estuaries and pockets seldom seen. But it seemed to stop as he mentioned the starlet’s name, the curiosity dried up when it was he who was to perform duty, but her friends whisper to her, what did she look like? I don’t know. She feels dirty somehow watching the funeral. She lets him touch her less and less, he is sure it is because of his occupation, she has superstitions, his hands are tainted.

Marilyn has a session with her therapist in the morning, she is tired and plays with her hair as he talks about her last marriage, her hair feels dry, straw-like, she has recently gone platinum, she’s sure it’s ruined her hair. They talk about transience and dependence, she thinks of Miller’s thin fingers, she feels indifferent. By noon she is on the beach with George Barris, she’s spent the last few days with him, snapping photos by the pool, before the desert fauna in her back yard, spiky leaves and hard colors, this fauna has been behind her, her entire life–it’s spiny and sharp, the men are similar, all angular and sharp, she’s not sure what this is about, tall, angular like Bobby, Joe, perhaps Jack’s features were too soft, blended, pudgy, pig nosed. She hasn’t remembered a day where she feels so happy as today, the morning is bright, the sea calm. She judges her happiness on continuum, coffee leads to alertness, water in the shower is fine, little panic about clothing, shoes are right, did she finish the amount of pages she was supposed too, what had she remembered, what had she learned, lunch doesn’t look good. Which foot feels right, which space is right, the drugs even out things but a staleness is still found beneath. She never swam as a child there was little time for that, we swim for pleasure and rest, not resistance of currents. She was raised to believe several things, several notions of thought and brevity, do we conduct ourselves like this or this? She is not misunderstood, that’s the funny thing, she’s just not here. She feels like a prop, a sleeve that isn’t adjusted properly, it’s too long, it’s short, it’s bunched at the elbow. There’s is a certain word that rolls about in her memory- bittersweet, someone described the feeling to her once at a party, wasn’t this when she met Bobby? It growled out to her like wounded beautiful animal scratching at her and she felt she had struck gold. It could be her word, if one were allowed to own a word. Sometimes she felt her tragedy was her ability to bend and groove herself within her fans, relinquish her statue, cripple herself on their stairs, their couches and beds, her being seem thrown about in cocktail parties and in the pecked kisses she often threw out.

The light is stark, chilly light, can light be chilly? But Marilyn seems content, she’s languid today, fluid so to say, slippery. He likes her beauty now better then before, she is more fragile, makeup cracks, fills in lines and lips are less plump – settled in their history, their story. There’s a scar below her rib cage, he sees it when she wears the bikini – there’s rumors of her health, her body seems a walking depository, men leave scents, disease lays dormant. They’ve seen each often these days, the stocky, jovial photographer stalking his lithesome prey, posing, evaluating, leaning towards subject – though by and large it is her environment, her own bright havoc. He seldom adjusts her, clothing is nestled only, brushed to sit easy, sometimes she just talks, swims in the mood and prowls within. She is the only woman he knows who carries order inside her disorder. She holds the weight of the world easily, an easy surrender she’s willing to bare. Perhaps his favorite photograph, after he gets home and develops in the darkness, in the tomb where starlet and fame aren’t allowed–is the photo of her on the beach this day, the orange bikini weighed down with water, seaweed like a cloak or a strange forlorn boa draped over the arm, she stands matter of fact, her makeup askew, her expression a comical annoyance. “These are my Champagne days,” she says, “There’s a future and I can’t wait to get it.”

He left the set of Cleopatra a week before,Taylor wasn’t difficult just prosaic, he wanted her to be more interesting, less tact or more show he wasn’t sure. She had a custodial manner as if she were the protector of the sets, the crew, her props, her gold and blue sceptre always with her. The headdress is comical, he loves its lavishness – its singular propriety. Her makeup was stark and bright, she fit the role well. Her beauty is different from Monroe’s – it’s a clean beauty, straight lines and stoic in it’s alertness. Marilyn is a sleepy beauty, drowsy, natural like salt water on the skin after a swim, Taylor’s beauty is thrown out and announced, beautiful but harsh. The sets on Cleo are overwhelming, he feels like Riefenstahl shooting Triumph of the Will but feels smaller as if the sets dwarf him, maim him or his camera. Floats and parades of Egyptians roll by him, Hispanic boys and girls, black boys from the city standing stoically on sphinxes.

Photographing their last day of photos, he’s brought more champagne and they sip and sink heels in the sand and the seagulls shriek overhead. She likes to see the people down the beach, they dot the beach like small insects and have no idea who she is. He feels if he called them over they wouldn’t know what to say nor do, they might stop and stare, not manage anymore. There’s a young family close by, a man, woman and two children but he can’t see faces only forms, the man is distant from the family and spends what seems hours in the water. In a few of the quick snaps of Marilyn, he sticks the figure of the man in the background, we see a blurry figure beyond her left ear as she stands lean and wistful. Another shot, she is laughing, it seems a genuine laughter, the blurred figure of the man is near her hip, swimming, a body forever buoyant near her hip. He looks out to the sea, and she isn’t there, she is gone from his peripheral vision, or gone entirely, has she drowned? He isn’t sure he wishes to be associated with a drowning of a movie icon, she is his to drift out to sea, she is his to capture for the world but how quickly she is gone.

Yogi, her face looks like that because she’s dead in those photos. When people die, blood sinks due to gravity, so the blood will leave its proper place post mortem to pool on whatever side the deceased is laying on. You can’t tell so much in black and white photos that its blood and might look like bad skin but the fact is its not that she looks like that because she had bad skin in life its post mortem lividity. The darkened places in those b&white photos are actually reddish to purple discoloration because its blood. Also she looks bloated because she IS because she is dead. Dead people bloat. Her neck was very swollen and an incision had to be made in back and the skin pulled very tight and sewn to make her neck look nice. Dead people bloat because fluids are leaving their proper places where in life they are contained. When we die fluids move. Gas is produced by bacteria consuming waste products and also the dead flesh. Various factors determine the amount of bloating and lividity. Know something about the physiology of death before you make statements like you did concerning photos of a dead person. Anyway if u didn’t know all that. Now u do. Study death a bit. Coz one day you will be dead too and so will I and we will be lucky if we manage to look that good in death. Not trying to be mean, just informative. And if I offend, I apologize, but these are facts that no one is really exempt from. We die. Our bodies do their death stuff. Also, our eyes will flatten because the fluid will make its exit from them as well. And all embalming fluid does pretty much is kill germs to keep them from consuming us because when the germs in us feed off us this contributed greatly to decomposition. Anyway, it is a shame that there are people who suffer so intensely within their own selves as to not be capable of coping with other own mind. You cannot escape yourself. I feel that. I despise my own company yet I am the one person I can’t get away from. There is no walking away. There is no throwing oneself out when you’re tired of your own stupidity or behavior. Hah funny how life is, the human condition and the “problem Of other minds.” Selah. Mahalo!

She looks awful in both photos. Thirty-six years old is young and she looks over 50. Her skin is terrible. I don’t see how this can be all caused by one night’s overdose. She was a beautiful young woman. It makes me think something else happened. Also, why were photos such of these allowed to be published? I would think autopsy photos would only be accessible to family and medical people involved. (Yet, I looked at these – I feel bad for seeing her in this condition).

The first photo is post autopsy, the second is pre autospy, the damage done during it is obvious in the first photo which is the one usually published, not the second one as she really looked at death.

Thanks for the story of Marilyn. She was a good person caught in the trap of the Hollywood scene of the time where mongrels ruled and people like Marilyn were the victims.

That was exactly what I was looking for. This one had me laughing for awhile: http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=gDRT8GgKlw0

The moment I found this was like wow. Thanks for putting your effort in making this site.